Designing England

Historic Architects and Architecture Through the Ages

From Roman forts and villas to Gothic cathedrals and the visionary works of architects like Inigo Jones, Sir Christopher Wren, and George Skipper, this episode of Big Blend Radio's "English Connection" Podcast with Glynn Burrows explores the evolution of architecture in England and what it reveals about wealth, power, craftsmanship, and society. (See his article below)

Through a thoughtful conversation on design, functionality, and opulence, we examine how architectural styles reflected social status, how many builders and artisans went uncredited, and how architects eventually emerged as cultural figures shaping England’s landscape. The discussion also raises deeper questions about legacy, meaning, and how future architecture may move toward more sustainable and purposeful design.

HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE IN ENGLAND

By Glynn Burrows

Architects have been around as long as people have been building buildings, but they have only been recognised and acknowledged for a few hundred years.

The Romans likely had architects who made all the calculations and drew up the plans for the construction teams to follow, but sadly, their names are not generally recorded. It is obvious that the Romans had plans, as all of their towns, cities, forts, villas, and many other buildings are laid out in a similar manner.

A fort on Hadrian’s Wall is similar to a fort on any of the other Roman borders. They were nearly always shaped like a playing card, with heavily fortified entrances on the four sides. There were living quarters for the soldiers and the area commanders, a hospital, a kitchen, a small bath and, most importantly, a barn for grain to feed the inhabitants if there was a siege.

Outside the fort, there were ancillary buildings like more baths, pubs, shops, houses, tradesmen’s workshops and all the other services required by a large group of people. The main kitchens, baths, tradesmen’s workshops, etc. would have been outside the fort because of fire risks, but the fort itself still needed these facilities inside for emergencies.

A Roman Villa is also often set out on a similar plan, with the same rooms and similar configuration, because, if you find a good layout, why not stick to it?

We see the same things when we move forward to Medieval times. Most Cathedrals, Priories, Abbeys and many Churches are laid out to set plans and, if an archaeologist finds a part of a Priory in his trench, as soon as he recognises what part he has, he can be almost certain where the other parts of the building are going to be.

Medieval Masons who built the Churches, Castles, Cathedrals, and all those other amazing buildings were following plans and designs drawn up by people who were brilliant mathematicians.

The Romans used arches with a single centre, meaning that it was semi-circular, but by the time the magnificent Cathedrals were being built in the twelfth century, the architects had realised that arches with two centres were just as strong, so they started building Gothic Arches, which were much more pointed.

By building different arches, buildings could be much wider and much bigger, as the arch was strong enough to support what was above it. To make them even stronger and to stop the sides of buildings from collapsing, we see the addition of buttresses, which were to support the colossal weight of the towering structures which were being constructed by the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

So, sadly, all of those magnificent buildings, which fill our countryside, were designed and built by people who we will never be able to acknowledge, but by the middle of the seventeenth century, architecture was a recognised profession and architects were being recorded, with their plans kept alongside many other documents, in various collections.

One name which appears in many scholars’ writings about early architects of England is Inigo Jones. He is often called the “Father of British Architecture”, living at a time when there were changes on all levels of society, he was perhaps extremely fortunate to have been in the right place at the right time, with the right skills and the right connections.

Born around 1573 in London, he was obviously a very talented artist, as he was sent to Italy to study drawing, and he must have been top of his class, because he was employed by the King of Denmark to design two of his palaces.

That job then gave him access to the King of England, as the two Kings were brothers-in-law! He became “Surveyor-General of the King’s Works, and that put him in charge of royal projects till the outbreak of the civil War, in 1642. He died in 1652

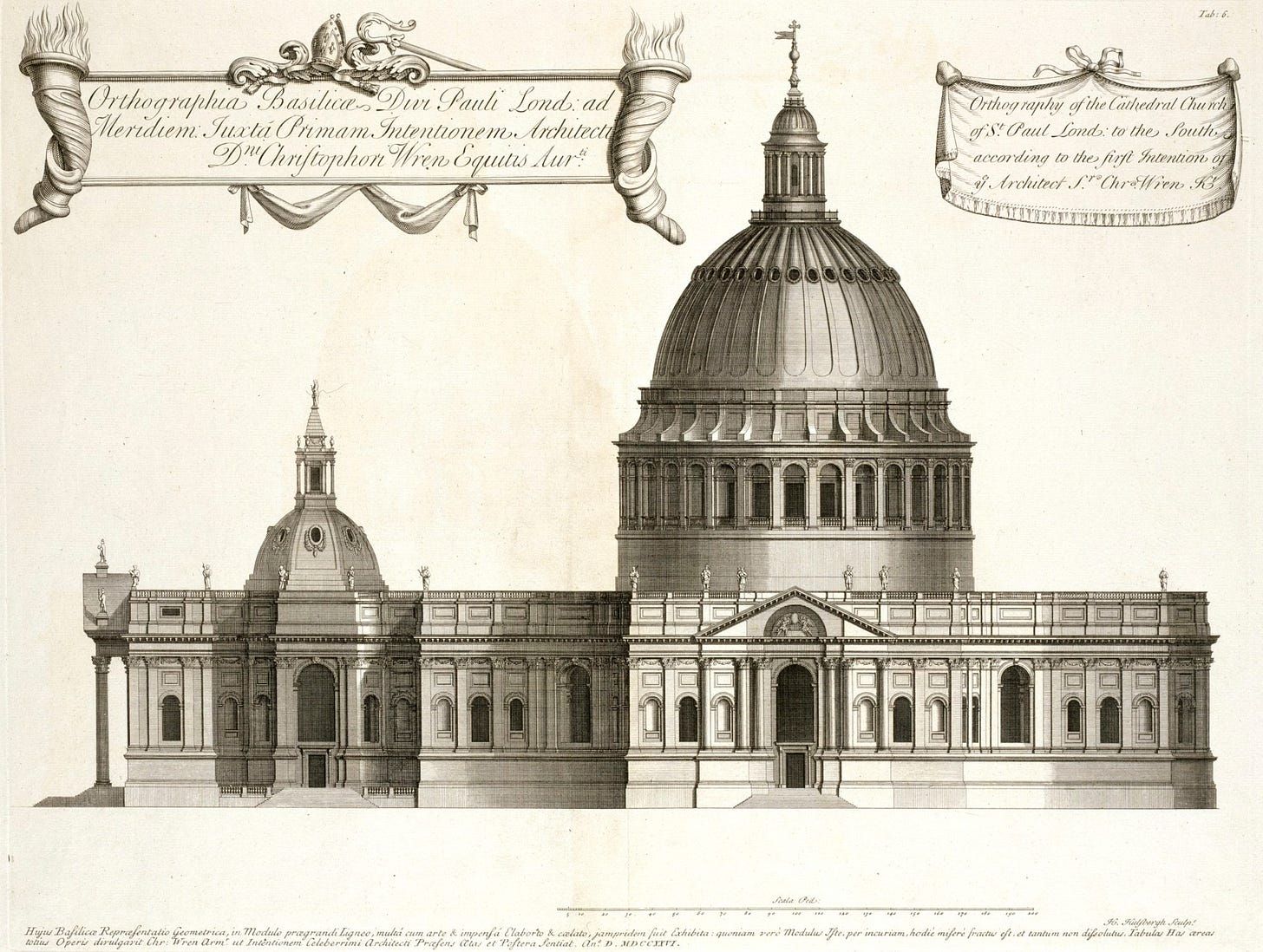

The next architect on my list is perhaps one of the best known, as his team was responsible for building over fifty Churches after the Great Fire of London, as well as St Paul’s Cathedral, several of the Oxford and Cambridge Colleges, The Royal Hospital at Chelsea, part of Hampton Court Palace and literally hundreds of other internationally recognisable buildings.

Yet another case of right place, right time, etc., young Christopher Wren was educated at home by his father and other members of the clergy, his father being a Rector. The appointment of his father to be Dean of Windsor meant that young Christopher spent part of the year in those affluent surroundings, although, as this was the time of the Commonwealth, it was a dangerous time.

Wren must have been a star pupil because he went to Oxford to study Latin. By 1657, he was Professor of Astronomy at Gresham College, London. His career took lots of twists and turns, with interests including Mathematics, Surveying, Meteorology and investigations into finding longitude at sea.

He became interested in architecture in the early 1660’s, designing a few projects, but in 1665 he took a trip to Paris to widen his skills and, when he returned, he started to work on redesigning St Paul’s Cathedral. Within a few days, the Great Fire of London destroyed two-thirds of the city, and Wren took his opportunity and submitted plans for rebuilding the city to the King.

The rest is history, and we have literally hundreds of Wren-designed buildings to visit. One of my favourites is the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford. An amazing building, with one of the best viewpoints in the city.

Sir Christopher Wren died in 1723, aged ninety and is buried in St Paul’s Cathedral.

My last architect is not an internationally renowned one, but is a local man, born just three miles from my home, in my local town of Dereham. George Skipper was born in 1856 and was the son of a local carpenter and builder.

His father’s business was very successful, as in 1861 he was employing twenty men, which enabled the family to send young George to school in Norwich and by the time he was 24, George was recorded in the census as an “Architect and Surveyor”.

George Skipper was designing buildings at a time of great affluence, and he wasn’t afraid of showing off the wealth of his clients. Some of his buildings hark back to ancient history, and others are completely up to date with the Art Deco and Art Nouveau styles coming in, using colour with the amazing porcelain tiling, which became so popular at the time.

It is interesting to see that, due to the industrial revolution and the subsequent mass production, the “new” fashions in building could be made available for everyone. I remember that many of the older cottages I knew had fireplaces with glazed tiles around them. Allowing even the poorest of society to enjoy some form of fashionable embellishments in their homes.

Looking at architecture as a subject for a tour could take you all over the country and also take in over two thousand years of history, from the Romans, through the Normans, Medieval times with those amazing Gothic Cathedrals, through the seventeenth century, with the rebuilding of London and the styles that introduced and the Georgians, Victorians and Edwardian periods, bringing in more easily accessible styles which could be replicated much more easily.

The serious architectural historian, studying any of the well-known, not-so-well-known architects, or anyone interested in a certain period of history, could easily fill a ten-day tour, taking in examples of work and possibly even staying in buildings designed by that chosen architect or built during a chosen period. Shipper, for example, designed several hotels on the North Norfolk coast, and one of the farmhouse bed & breakfast establishments I use was built as a College for Medieval Monks in the 14th century.

One last thing, though. If you do visit the UK, look up above the shop-fronts in cities and towns, as the architecture of the past is often still there in plain sight.

Glynn provides customized, private tours and also helps his clients trace their English family history. Past guests have visited and experienced stately houses and gardens, castles and churches, ruins and villages, birding and wildlife, World War II airfields, and general area taster tours too. Accommodations can be in all types of establishment, from character buildings such as windmills, thatched cottages and castles, self-catering or five star luxury – just say what you want and it can be arranged. Nothing is too much trouble for Glynn! Visit www.Norfolk-Tours.co.uk